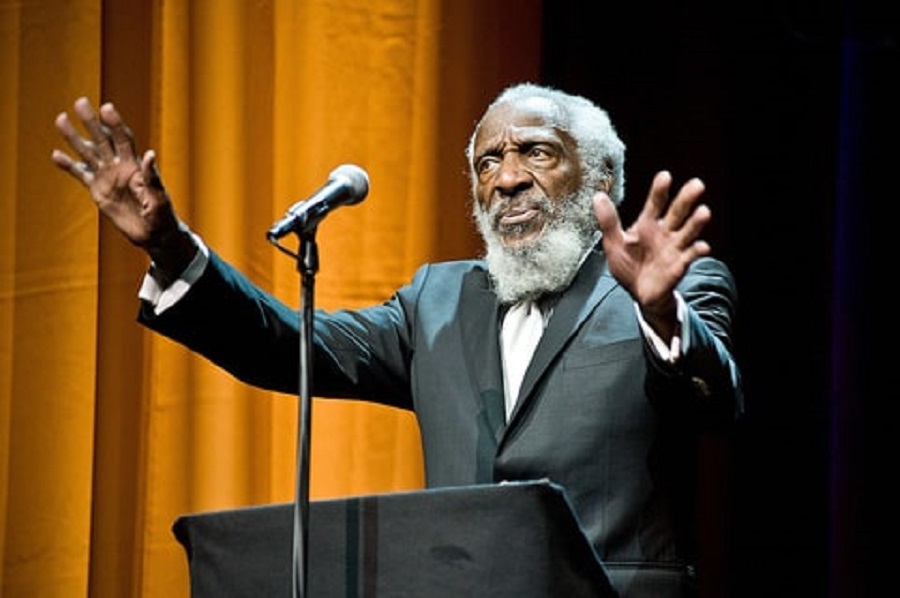

Comedian and activist Dick Gregory died Saturday. Gregory died following a severe bacterial infection, after being in and out of the hospital.

Fans and friends took to social media to honor the late comedian and civil rights, crusader.

Farewell, Dick Gregory

Dick Gregory, who was recently diagnosed with a severe bacterial infection, died in Washington DC.

The 84 years old comedian and activist is survived by his wife, Lillian, and 10 children.

His family announced the sad news via social media.

“It is with enormous sadness that the Gregory family confirms that their father, comedic legend and civil rights activist Mr. Dick Gregory departed this earth tonight in Washington, DC.” his son Christian Gregory said in the post.

“The family appreciates the outpouring of support and love and respectfully asks for their privacy as they grieve during this very difficult time. More details will be released over the next few days.”

Gregory remained active on the comedy scene until recently. When he fell, ill he canceled an August 9 show in San Jose, California, followed by an August 15 appearance in Atlanta.

On social media, he wrote that he felt energized by the messages from his well-wishers. He was looking to get back on stage because he had a lot to say about the racial tension brought on by the gathering of hate groups in Virginia.

“We have so much work still to be done, the ugly reality on the news this weekend proves just that,” he wrote.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BYAwkw2j_1g/?taken-by=therealdickgregory

Breaking the ground

Richard Claxton Gregory was born in 1932, the second of six children. His father abandoned the family, leaving his mother poor and struggling.

Though the family often went without food or electricity, Gregory’s intellect and hard work quickly earned him honors. He attended the predominantly white Southern Illinois University.

“In high school I was fighting being broke and on relief. But in college, I was fighting being Negro,” he wrote in his 1963 book.

He started winning talent contests for his comedy, which he continued in the Army.

After he was discharged, he struggled to break into the standup circuit in Chicago, working odd jobs as a postal clerk and car washer to survive.

His breakthrough came in 1961, when he was asked to fill in for another comedian at Chicago’s Playboy Club. His audience, mostly white Southern businessmen, heckled him with racist gibes, but he stuck it out for hours and left them howling.

That job was supposed to be a one-night gig, but lasted two months — and landed him a profile in Time magazine and a spot on ‘The Tonight Show.’

A life of activism and change

Once in the spotlight, Gregory used his humor to spread messages of social justice and nutritional health. An admirer of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., Gregory embraced nonviolence and became a vegetarian and marathon runner.

He preached about the transformative powers of prayer and good health. Once an overweight smoker and drinker, he became a trim, energetic proponent of liquid meals and raw food diets.

Hunger strikes were a frequent activist tool for Gregory.

Gregory went without solid food for weeks to draw attention to a wide range of causes, including Middle East peace, American hostages in Iran, animal rights, police brutality, the Equal Rights Amendment for women and to support pop singer Michael Jackson when he was charged with sexual molestation in 2004.

“We thought I was going to be a great athlete, and we were wrong, and I thought I was going to be a great entertainer, and that wasn’t it either. I’m going to be an American Citizen. First class,” he once said.

He persisted in the political world

He briefly sought political office, running unsuccessfully for mayor of Chicago in 1966 and U.S. president in 1968, when he got 200,000 votes as the Peace and Freedom party candidate.

In the late ’60s, he befriended John Lennon and was among the voices heard on Lennon’s anti-war anthem ‘Give Peace a Chance,’ recorded in the Montreal hotel room where Lennon and Yoko Ono were staging a “bed-in” for peace.

At the time, he was also leading voter registration rallies in Mississippi and taking part in anti-segregation protests in Alabama.

“If we are successful with this revolution, people all over the world are going to recognize what we did to the greatest nation of the world without firing a shot,” Gregory told students at one of the anti-segregations protests.

He was direct in his language about race. He co-wrote with Robert Lipsyte the book ‘nigger: An Autobiography ‘— the “n” is lowercase — in 1964. Gregory explained to NPR why he chose that title:

“So this word ‘nigger’ was one of the most well-used words in America, particularly among black folks. And I said, `Well, let’s pull it out the closet. Let’s lay it out here. Deal with it. Let’s dissect it,'” he said.

“Now the problem I have today is people call it the N-word. It should never be called the N-word. You see, how do you talk about a swastika by using another term?”

Source: News Wabe